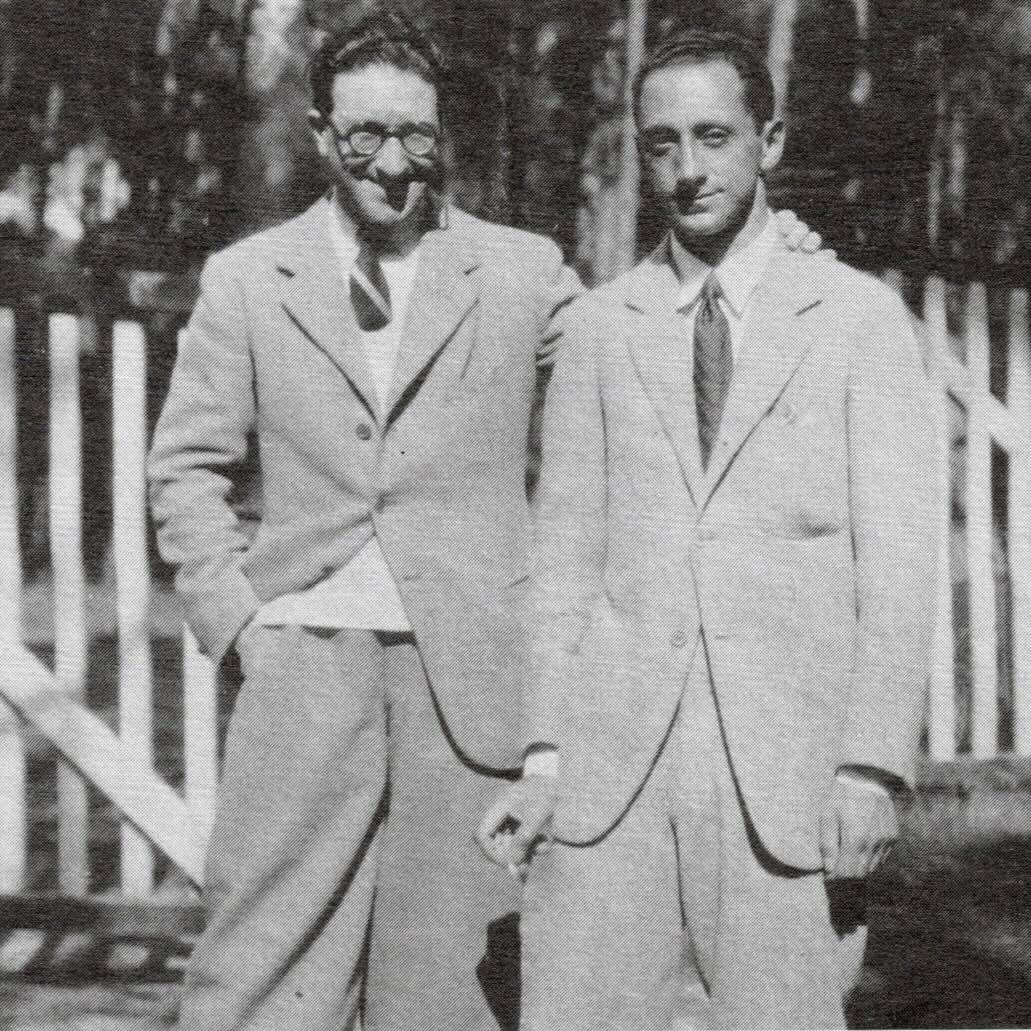

Emilio Terry (1890-1969)

Architect, designer, decorator and landscape architect, Emilio Terry (1890-1969) was a unique figure in the world of decorative arts between the two world wars. The heir to a prominent Cuban family, educated in the cosmopolitan and intellectual circles of Paris, Terry designed architecture and furniture freely inspired by classical references, from Palladio to Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, while infusing them with a taste for poetic strangeness. He thus forged the concept of the ‘Louis XVII style,’ an expression of an imaginary classicism, never truly historical, but always evocative.

View full biography

The influence of French heritage, particularly the Château de Chenonceau, owned by his family, was also decisive. Terry was marked by Philibert Delorme‘s design, with its enfilade galleries, majestic proportions and neo-antique ornamentation. This place nourished his taste for French art inspired by Italy, steeped in symmetry, refinement and erudite references.

Emilio Terry was self-taught in his artistic practice. The war prevented him from studying at the Beaux-Arts, which kept him at a distance from the academic eclecticism of the time. He immersed himself in the great Italian architectural treatises of Palladio and Vignola. In this way, he developed a deeply personal style, nourished by an admiration for the visionary, utopian and grandiose architecture of the late 18th century.

His creations spanned all areas of the decorative arts: furniture, objects, carpets, houses and gardens. Among his first notable works was the Monogramme sideboard (1928), made of cast aluminium, which already showed his taste for powerful and symbolic forms. He also created a ‘rocky’ console table (1926) for the Château de Clavary, inspired by the holy water fonts of Pigalle in Saint-Sulpice, and a Restoration-style table inlaid with precious wood, which remained at the Château de Rochecotte for many years.

In the 1930s, a period of upheaval, Terry pursued a unique path: he proposed architecture that borrowed from nature — rocks, shells, drapery — not as ornamentation, but as the very building blocks of the walls of the dwelling. For him, function arose from beauty: architecture had to deliver a ‘truly human’ message, combining poetry and formal rigour. But it was also during this decade that he began a decisive collaboration with Jean-Michel Frank, master of minimalist luxury. In this fruitful synergy, Emilio Terry rubbed shoulders with Alberto Giacometti, Christian Bérard and Paul Rodocanachi, and contributed to the creation of iconic pieces of furniture, such as a neoclassical bench and a wooden console table, designed for Frank’s boutique, which opened in 1935.

In 1933, his drawings were exhibited at the Jacques Bonjean gallery, frequented by de Chirico and Dalí. In 1936, some were included in the famous exhibition ‘Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism’ at the MoMA in New York, confirming his place among visionary creators, halfway between classical utopia and poetic surrealism.

He also designed refined interiors, such as that of the Basque house Calaoutça for Princess Bibesco, in collaboration with Jean Hugo, a descendant of Victor Hugo. But he also imagined ideal architectures, such as his spiral house, a model of a double-spiral dwelling, reflecting a concept in which architecture is no longer a framework, but a dream that can be lived in.

Rediscovered late in life, Emilio Terry is now a cult figure in the world of dreamlike and erudite decor, at the crossroads of classicism, utopia and surrealism.