Line Vautrin (1913-1997)

Born in Paris in 1913, Line Vautrin was a French artist, designer, jewellery maker and creator of decorative objects. A unique and fiercely independent designer, she created objects of intense poetry in the Paris of the immediate post-war period.

View full biography

Line Vautrin, HER ORIGINS

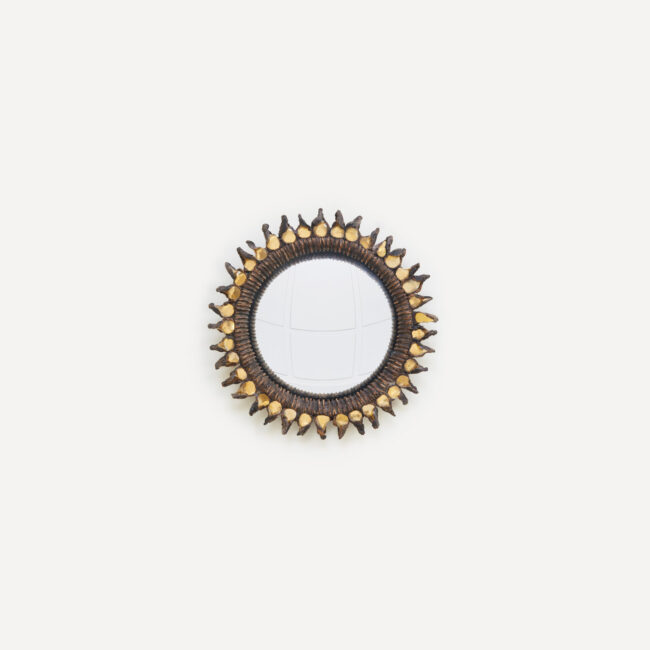

Line Vautrin began devoting herself to creating objects at a very young age, producing her first works when she was just twenty-one. At the 1937 International Exhibition of Arts and Technology, she had a stand where she presented her creations, which included powder compacts, boxes, brooches, necklaces and ashtrays in gilded bronze, engraved or enamelled, belonging both to the art of jewellery, through their delicacy, and to sculpture, through their tactility. She was very successful, which enabled her to quickly build up her first clientele. Initially based in a tiny premises on Rue de Berri in Paris, her success enabled her to open a boutique on Rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré, in the couture district, before transforming 106 Rue Vieille-du-Temple.

HER CAREER

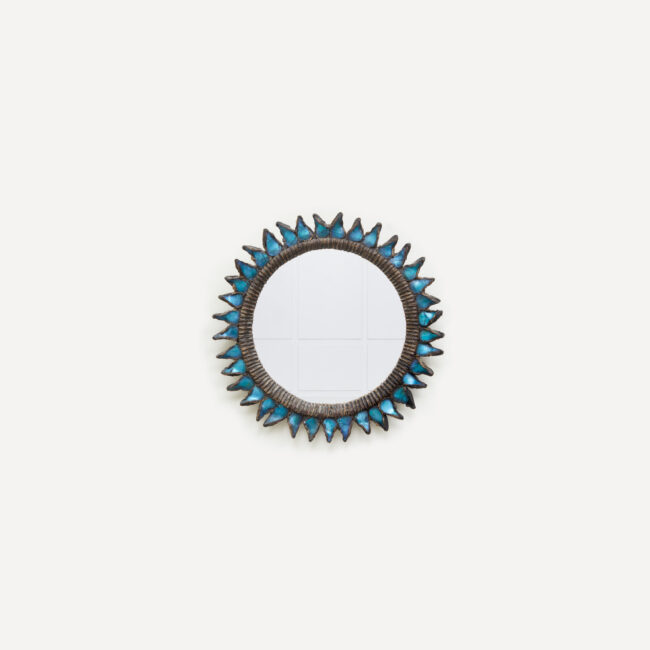

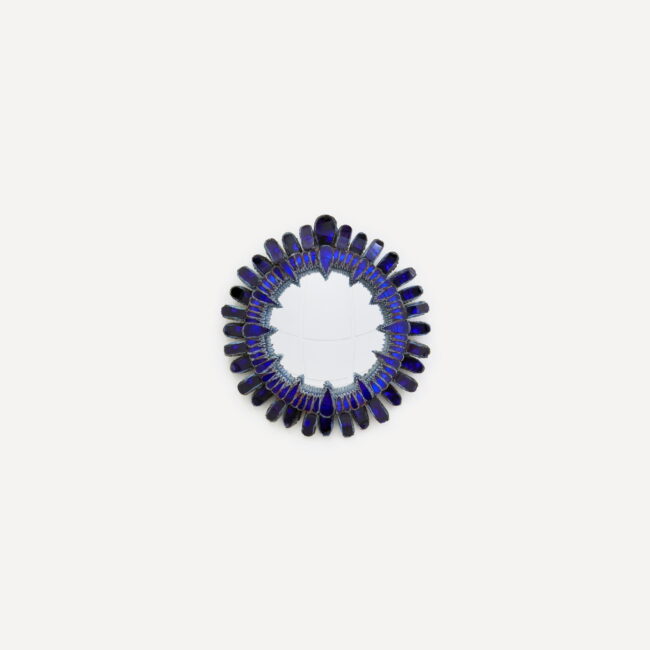

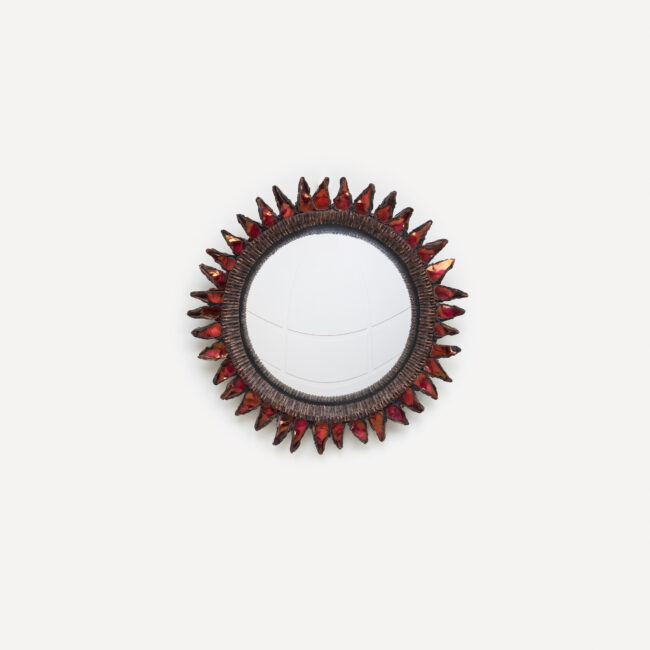

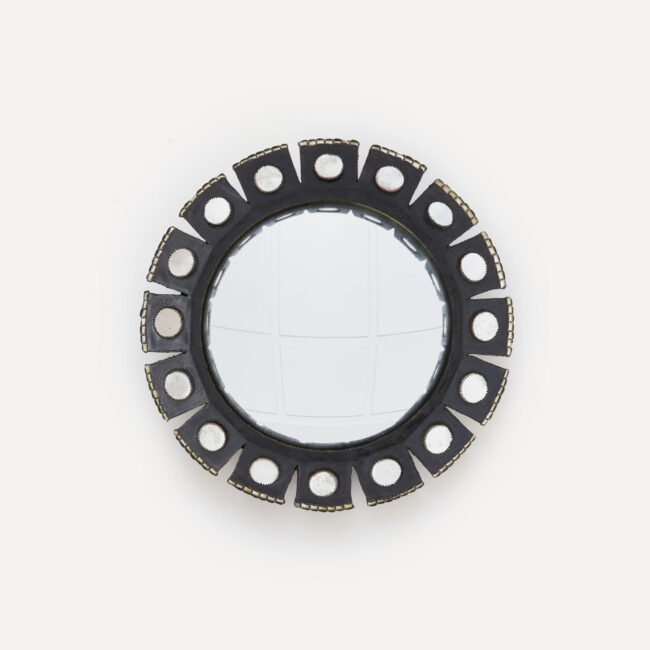

In 1953, Line Vautrin, always on the lookout for new ideas, filed a patent with the INPI (Institut National de la Propriété Industrielle) for the discovery of a mysterious resin, cellulose acetate, which was extremely resistant. She named it Talosel in the late 1960s when she moved to Quai des Grands-Augustins. It consists of thin sheets of resin, arranged in layers, scraped and scarified, worked with fire, inlaid with thin shards of mirror, taking on the most subtle shades, evoking slate or schist, bone and wood worn away by time.

Following this discovery, Line Vautrin never stopped transforming materials. She created her famous sparkling, poetic mirrors that distort reality through their witch, a convex mirror forming the center of her creations. She quickly became a huge success in France and internationally. In the 1960s, she also used talosel to make chests, sconces, lamps, frames, coffee tables, screens and chandeliers. Line Vautrin also returned to her early days as a jewellery designer, replacing gilded bronze with talosel. She created necklaces, bracelets, earrings, brooches and cufflinks, made entirely of talosel inlaid with mirrors.

In the June 1948 numero of Art et Industrie, Line Vautrin explained her principles: “I believe that most of the time, it is rhythm that drives me to do something, and then the idea somehow becomes incorporated into these volumes, these swaying surfaces… I could say that instinct is expressed through rhythm, intelligence through the storytelling that is grafted onto it, whether intentionally or not, and sensuality through modelling. When you touch a model, it should give your fingers satisfaction; it should not be jarring. The hand must judge as much as the eye.”

In 1998, the Chastel-Maréchal Gallery devoted its first major exhibition to Line Vautrin. In 2004, the gallery once again organised an exhibition of the French artist’s work, mainly featuring mirrors but also gilded bronze objects. On this occasion, the gallery published a monograph which is now the only reference work on Line Vautrin’s mirrors.

Since its inception, Chastel-Maréchal Gallery has shown a strong interest in and attachment to the work of Line Vautrin. The gallery has contributed to the artist’s renewed recognition, as well as to the explosion of her value on the market, which continues to rise. Her works, particularly those made from talosel, are highly sought after and fetch very high prices today.

Line Vautrin is now part of the history of 20th-century decorative arts, and her creations feature in the most important international sales and in the collections of the world’s greatest collectors.

Nevertheless, Chastel-Maréchal Gallery focuses on seeking out the rarest designs, colours and shapes in order to offer only exceptional pieces.

To better support its collectors, Chastel-Maréchal Gallery guarantees that it will ensure the proper conservation of the pieces it sells.

Line Vautrin seen by Patrick Mauriès

Line Vautrin seen by Patrick Mauriès

From the outset of her career, Line Vautrin’s work, in its very diversity and variety of media, has been stretched between two essential poles: gilded bronze objects, on the one hand, where plasticity is generally inseparable from a play on language, proverbs, popular wisdom and a few poetic fragments; and, on the other, a more singular and intimate focus on lacquers and resins, which took on various names and forms over time before finding a definitive formula in the early 1950s.

In 1953, she concentrated her efforts on a new technique, which she initially dubbed ‘Oforge’. ‘The first letter,’ she explained to a journalist in 1958, “as I drew it, symbolises the sun. I have always been obsessed with suns… But the sun is also fire. As for “forge”, it is the symbol of working with fire. But to this fire, I add water, which is purity, calm…

Oforge essentially consists of an alloy of two materials: glass or mirror (tinted or untinted) in the form of fragments amalgamated by a plastic binder, embedded in the plastic so that only a surface of glittering flakes or scales appears in a solid mass. Thus created, Oforge symbolises the union of fire, which melted the material, with water, represented by the transparency of the glass. […]

Her mirrors and jewellery are sold in various shops in Paris and the provinces; she is back in the interior design magazines; architects such as Jean Royère and interior designers such as Jean Dive use her creations in their own projects.

When she moved to Quai des Grands-Augustins in the late 1960s, her entire flat became a veritable showroom: resin was not only used for the mirrors that adorned the walls, but also covered chests, sconces, frames and coffee tables, even the ceiling beams, set with boxes imitating 16th-century decor in shades of brown and burnt earth. In the meantime, the process has found its definitive name, which has been trademarked: ‘talosel’. […]